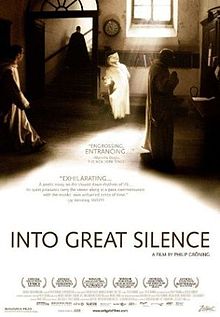

INTO GREAT SILENCE

Germany, 2005, 168 minutes, Colour.

Directed by Philip Groning.

One of the frequent themes of books, television programs and films is the too rapid pace of modern life. Everything is meant to be instant, and faster. Here is a film which advocates slowing down, reflecting on the meaning of life, meditating and praying as a powerful means of coping and finding meaning in one’s life.

The director, Philip Groning, approached the Carthusian monks of Grand Chartreuse in the 1980s for permission to film them. They held out until some years ago. They feel that they are ready now to be seen.

Groning and his crew lived for several months with the monks, observing and filming as well as sharing many of the routines of their daily lives. The result is a long film (two hours forty minutes, a challenge in itself) where the measured pace is an invitation to audiences to pause, sit back and absorb the atmosphere of the monastery.

It should be said that Groning is also a photographer and has delighted in the environs of the monastery, the changes of the seasons, the tones of lighting for the different parts of the monastery. To that extent, the film is like a visual coffee table book of monasticism. (And, as the publicist remarked to me when I made this point: it’s a hardback, not a paperback.)

The Carthusians were founded by St Bruno in the 11th century at a time when there was a movement of reform in the long-established Benedictine monasteries. St Bernard founded the Cistercians at this period. The silence and slower pace of monastic life were re-emphasised. Communal life was centred in liturgical prayer and silent meals, the monks having more time to read and to spend contemplation time in solitude.

Audiences are invited in to observe the monks and this way of life. It is not offered in any chronological way, say from morning till night. Rather, we dip into different facets of the life, glimpses, some repetition, some close-ups of particular monks, some outside scenes of work with the monastery’s brothers, some mundane aspects like haircuts and some rarer examples of recreation, walks in the countryside, some tobogganing on the wintry mountain slopes.

There is very little talk in the film (although some scripture texts are repeated like the response to the psalm at Mass).

For those not familiar with monastic life and its meanings, this will be an interesting and challenging look at a different, a counter-cultural way of life. A film on a Buddhist monastery or on Sufi spiritual gurus would have a similar effect.

For those familiar with the Catholic tradition, there is some puzzlement. Because of the lack of dialogue or conversation with the monks, we have to try to work out what they actually understand by prayer and contemplation. There are no explanations from the monks (except some very detached observations at the end about accepting and rejoicing in suffering from a blind monk) as to why they are there and what keeps them going.

While there are a number of sequences in the chapel for the chanted recitation of the Divine Office, it is only in the final part of the film that we see any Eucharistic celebration which, in the spirituality of any order, would be the centre of monastic life and personal devotion. In fact, while the film leaves audiences to supply their own image and understanding of God, the film is also surprisingly reticent about the place of Jesus in Carthusian spirituality.

While it has won awards in Europe and had quite long runs in countries like Germany, Holland and Luxembourg, it is hard to predict how audiences will respond to a long film about contemplation.