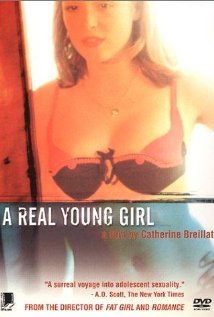

A REAL YOUNG GIRL

France, 1976, 90 minutes, Colour.

Charlotte Alexandra, Hiram Keller, Rita Meiden, Bruno Balp, Shirley Stoller.

Directed by Catherine Breillat.

When it was first made in the 1970s, French officials banned the film from public screening, with its sexuality topic, the sexual awakening of a teenage girl, as well as the very explicit close-ups of bodies and sexual activity.

It was based on a novel by the director, Catherine Breillat, who began a 40 years long career in making films that were particularly explicit, usually tackling sexually provocative themes. They include Romance, Sex is Comedy, And Anatomy of Hell, and more successfully dramatic films like A Ma Soeur and The Last Mistress.

It is not surprising to find that this was the director’s first film. In many ways, the film-making is very basic, standard setups, close-ups, and an editing patten that is too strong on fadeouts, highlighting how little many of the sequences lead into the ensuing sequences. While the framework is of a summer holiday, the young girl, Alice, returning to her home and farm, bored with nothing to do, preoccupied with herself, her body, sexual functions, and a belated attraction to a young man, Hiram Keller (star of Fellini Satyricon), who works at the mill. She is antagonistic towards her mother, who controls the household, is busy tidying things up, cooking and reprimanding her daughter whom she considers a failure. The father is much more good-natured, working in his garage, under the control of his wife, yet having a young girl on the side (with a few more explicit sequences and body glimpses) and a final confrontation with his wife. He seems devoted to his daughter.

The film is set in the 1960s and there is some allusion to political difficulties with the end of the era of Charles de Gaulle and references to the war and Petain and the Vichy government.

After many decades, the film scarcely seems provocative given so many other films of this nature and of the director’s own series of films. It does not seem particularly helpful in terms of psychology, even with Alice looking at herself, fingering herself, and all kinds of implements for sexual arousal. Whether she is any the wiser, we do not know – and there is a melodramatic ending when, suddenly, Hiram Keller is found dead.

Probably, the film contributes little to understanding of psychology and sexology – and it is more a film of historical interest because of the work of Catharine Breillat.