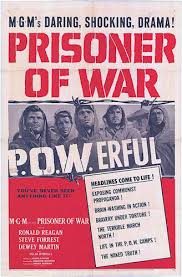

PRISONER OF WAR

US, 1954, 80 minutes, black and white.

Ronald Reagan, Steve Forrest, Dewey Martin, Oscar Homoljka, Robert Horton, Paul Stewart, Harry Morgan, Daryl Hickman, John Lupton, Jerry Paris.

Directed by Andrew Marton.

Prisoner of War is of historical interest. It was made at the end of the Korean War, still capitalising on animosity of the United States towards North Korea towards China. It also focuses on the plight of prisoners of war, discovering how much brainwashing techniques were used on them – as seen in some films like The Rack and, more importantly, The Manchurian Candidate. There is much talk of breaking points and referring to Pavlov’s responses and control.

In retrospect, it is interesting to see the attitude towards North Korea in the mid 1950s, continuing on throughout the decades and well into the 21st century. The film highlights the isolation of North Korea and its communist ethos, and the assistance of Russian advisers during the war.

And, also in retrospect, the film is interesting because of its star, Ronald Reagan, taking a strong stance in an anti-Communist film, at the time of the blacklisting and the Mc Carthy hearings, a quarter of a century before he became president. Some of his lines sound like the lines he used as President in the 1980s.

He was always a sturdy, often genial presence in films, especially in the 1930s and early 1940s at Warner Brothers. He plays an officer, asked to volunteer to parachute into Korea, join the prisoners of war, discover how the prisoners were treated, brainwashing techniques, and find ways of sending the information to America.

Steve Forrest portrays a very staunch pro—American, willing even to die for his beliefs with no concessions to the enemy. He also kills the Russian adviser, played by Oscar Homolka, who insinuates himself into the mentality of the Koreans as well as the Americans. There is a comic touch with his assistant who always answers his observations and commands with, “Yes, indeed”.

The character played by Dewey Martin is particularly interesting, a young man who seems to be at ease and accepting the blandishments of the Russians, for more food, for being in charge of the soldiers, the being the go-between the Korean authorities and the Russians with the soldiers. He is looked on by most, but others make concession for his inexperience and young age. It is a surprise the soldiers – and the audiences well – to find that he has been on the same undercover mission as Ronald Reagan, ingratiate himself, discovering information, communicating it back home.

The Ronald Reagan character also has to find ways to accommodate with the authorities and to get the use of means to get messages back to the United States. Martin had written letters home. He is filmed, as is Reagan and the audience sees the American authorities, led by Harry Morgan, in interpreting the information.

There are some scenes of cruelty, of one officer with his arms over a bar and his hands weighed down by stones with the authorities dragging on them. When the soldiers riot and destroy the film, they are all put into graves and left exposed until the day sign a document saying that they were not tortured. They are lined up to be shot. And Steve Forrest, the leader, is put on the hill with a kind of crucifixion.

The film was directed by Andrew Marton, himself from Hungary, migrating to the US at the outbreak of World War II. He made a number of films in different genres but is best known for his Second Unit work on Ben Hur and the chariot race.

This kind of history seems very remote in the 21st century, but it is an interesting example of propaganda, the dramatisation of American attitudes, especially towards North Korea.