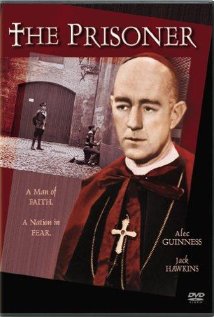

THE PRISONER

UK, 1955, 91 minutes, Black and white.

Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Wilfred Lawson, Kenneth Griffiths, Ronald Lewis, Raymond Huntley, Mark Dignam, Jeanette Sterke.

Directed by Peter Glenville.

Bridget Boland’s play, The Prisoner, was a success on the London stage in the early 1950s, starring Alec Guinness and directed by Peter Glenville, who worked together for the film version of 1955. The inspiration for the film came from the show trial of Cardinal Joseph Mindzenty of Hungary in 1948. This is a fictionalised version, showing the State’s interrogation of the Cardinal and working on him through psychological pressure rather than physical torture, as actually happened with Mindzenty.

The film is quite theatrical, a two hander between Alec Guinness as the Cardinal and Jack Hawkins as the interrogator. The film sometimes goes out into the streets and there is, at least for the main plot, a superfluous romance. The film was considered too controversial in 1955 to be accepted for the Cannes and Venice film festivals.

Twice in the film, the sentence “do not judge the priest by the priest” is spoken, at the end by the Cardinal himself. However, The Prisoner offers a very interesting portrait of priesthood in the 1950s and its meaning through the trial of the Cardinal, his interactions with his interrogator and his final absolute confession in court.

The film opens with a very solemn entry into the cathedral, a clerical procession in full robes, servers, ministers, the Cardinal celebrating mass for a devout congregation – but it includes the secret police, and a note hastily written and brought up to the Cardinal with the lectionary to warn him that the police are there to arrest him. He continues with the ceremony, leaves the cathedral, venerated by the peope, and is arrested. The charge is treason. As he is led away, the Cardinal advises that whatever confession he makes, it will be a lie or as a result of human weakness.

Cardinals are considered, or were considered, Princes of the church. the following sequences where he is taken away in the car, brought into prison, treated according to prison regulations in detail, would have been more shocking than they would be now. He gives up his episcopal ring and cross – with a comment from the warder “that’s where the money goes” and the jibe that the jewelled cross has been paid for by money from the poor box. The prisoner is fingerprinted. He is taken to an austere cell.

The character of the Cardinal is made clear, a strong priest, a hero of the resistance, a stalwart against torture, now representing religion, an organisation, as his interrogator asserts, outside the state, meaning that the pulpit is a dangerous monument and must be defaced or destroyed. The Cardinal asserts that he will not be trapped, that he is tenacious, wary and proud, tolerably iniured to physical pain. The interrogator offers to bring the completed confession for him to sign to save time. Or, it will be an agenda to work from.

In the cell, a bright light is always on, there is a spy hole for observers to look in, he may talk only to the interrogator and the warder, not even to the doctor who comes to examine him.

As the interrogation progresses, and is recorded (and it is later shown being edited), the Cardinal replies in witty ways, “you want a confession, not the truth” and, when the interrogator drinks from the coffee offered, the Cardinal accepts and toasts “my health”. The interrogator has been a doctror, says that it is the mind of the prisoner that he wants, the weak spots, to effect a conversion. He is being pressurised by higher authorities to discredit the Cardinal as quickly as possible since they would prefer physical torture rather than long-term psychological brainwashing.

While the Cardinal prays “God give me cunning against your skills”, he also defends himself against being called an enemy of society, schizoid, paranoid, misleading the week, the poor and the silly, by reminding the inquisitor that his answer is to render to God what is God’s and to the state what is the State’s. There is a visual collage of the Cardinal been questioned, the tapes, the investigator relaxed, the powerful cell light, the Cardinal pacing, in the courtyard, up and down steps.

As the investigator begins to probe the Cardinal’s personal life and his vocation, he states that he is not like the Gestapo but wants to discover what cannot be used against the Cardinal. As a boy, the Cardinal had a hard life, going each day to the fish market, fish eyes sticking to his boots, wearing only overalls, wanting soap and disinfectant to get rid of the smell. Then he faced the dilemma, the winning of a scholarship and following through on his vocation, the Cardinal saying he had always known that he was called to be a priest but had tried to evade it because he was not worthy. He emphasises that he had to be a priest, to shirk nothing, to doubt nothing, to overcome everything.

His time at the church of St Nicholas, his first curacy, is also probed. The parish was poor, political and the interrogator taunts the Cardinal about preaching to the people, Thou Shalt not Steal, accusing him of stealing which he confesses: books for his exam, paper and pencils, through ambition rather than need, always taking the best.

The authorities organise a pre-trial meeting, urging him to plea for mercy and to plead guilty. He shown a map, but is able to highlight that images, his signature and writing are really a cut and paste job. When the doctored tapes are played for him, he points out the different sound levels in the recording. The authorities are humiliated by his astute interpreting of what they have prepared.

Yet, the interrogator says that the process must end in tragedy and then brings in the covered body of the Cardinal’s mother, the Cardinal praying, the interrogator urging him to bless her, which, surprisingly for the audience, he finds it difficult to do. He talks about his body and her body being one, kissing her hand, finding it still warm and being told that she has been anaesthetised, with a threat of her being taken to the Research Centre. What emerges is that the Cardinal could say that he does not love his mother, never has – the interrogator saying he was disgusted, that he now did not dislike his work and that the Cardinal was a hard man. The Cardinal is returned to solitude, the interrogator playing chess, waiting.

In his cell, the Cardinal continually polishes the floor, lies down to catch glimpses of any life under the door, bangs the table, tears the cloth, is both fierce and exasperated, reciting maths tables, singing the hymn for the dead, Dies Irae, losing a sense of days, the window being boarded-up and his not knowing whether it was day or night, time for sleep or not. The warder taunts him by bringing him a tin of polish and a cloth, indicating that could stay and rot there forever, with a story about a prisoner who took a mop to bed and stroked its hair. Times for his meals are erratic, long periods, then five minutes, a solitary confinement to send a person out of his mind, lose his wits, frighten himself to death.

The interrogator bides his time, starts to offer falls friendship, allows the Cardinal a sedative, but now feels that he can “play him and land him” but wants the trial within 48 hours. The tack taken with the Cardinal is that he hates himself, that the interrogator knows and understands him but does not hate him. He asserts that the Cardinal does not live his fellow men, has no delight in his God, that his heroism in the resistance was merely to prove himself. The Cardinal states that the flesh is weak, the interrogator picking up possibilities about sexuality in the corners of the Cardinal’s mind, thinking life has been a facade, asking what he is hiding and what he is ashamed of. The answer is that he is ashamed of his mother, the fact that he was legitimate but that his mother saw men behind the fish market and that everybody knew, that as a boy he listened to the new feet, to the laughing and whispering. So, he wrapped his body in a cassock, aiming for success to justify his pride, no love to his mother, but shame for her sin.

He thought to kill himself, but the scholarship and the University were second best. The best was to serve God, because as a priest he wanted to start again, feel free, feel clean, justify himself to himself rather than to God – and he succeeded, “I could serve God, myself, my country, but I can’t care”.

This is the key for the interrogator, accusing the Cardinal of being a fake, a diatribe against him for making his life in the church something to serve his own pride. He then taunts him about restitution by telling the world, telling everyone that he betrayed his comrades during the war, that he was so certain of himself, his wits and his sacred hands, his insufferable conceit. The Cardinal must confess without drugs, hypnosis or hysteria and to give back in his own way.

The actual trial follows, the judges, the prison personnel, the interrogator taking the role of the prosecuting lawyer, many of the sequences filmed from above, giving the audience a wide view of the Cardinal and his tormentor in the centre, surrounded by hostility.

He confesses to glory and ambition, to the misuse of money, to the use of secrets from the confessional and selling them to the police, being linked to the Gestapo, to having betrayed everyone. To each of the accusations, the Cardinal confesses.

In the aftermath, with newspaper headlines against him and the interrogator being the hero of the higher, the Cardinal says that he would prefer to go mad. Speaking with his assistant, the man who edited the records, who advises his boss not to be squeamish because that would spoil his triumph, the interrogator admits that he had played on the Cardinal sense of pride – but that he was truly humble: a truly proud man would have been far more sceptical in the face of the accusations.

The Cardinal is to be executed, is given a final meal, requests to see a priest which is denied, only to find that his sentence is not only to be commuted but that he is free to go, that his mother was already in the Research Centre when she had been brought in. The Cardinal, who had wished momentarily for death when the interrogator visits him and produces a gun, opts to face the world outside, that he must, that he could well live on 20 or 30 years more. Once more in Cardinalatial robes, he walks out of the prison, crowds outside make way for him to pass through as he walks towards the Cathedral.

The Cardinal triumphs through his humiliation, the words that he said about a confession being a lie or the result of torture once more in his mind and the comment for all not to judge the priesthood by the priest.

There have been many martyrs in every age, bishops and priests executed by authorities who considered them a danger to the state, in Roman times, to Thomas a’Beckett, to the many clergy arrested, tortured, killed by Communist regimes, especially in Eastern Europe or, later, in China and Vietnam. The stories are usually told as heroic stances for faith. This story works on the human level, psychological, emotional. The Cardinal has to face his own self and the authenticity of his vocation, matters which, in recent decades, would be part and parcel of psychological testing and guidance on discernment during seminary years. Watching The Prisoner now means an admiration for heroic responses in the past, but a realisation that for the authentic living off priesthood, the complex background of the priest’s life needs to be explored, acknowledged, and in some way, transcended.

For those unfamiliar with the details of investments and rubrics at the time, the film offers accurate representation.

1. A film of the 1950s? Europe, the Iron Curtain? Hungary? Communism? Anti-religion, anti-Catholicism?

2. The film based on a play, keeping the scenes’ structure, the dialogue?

3. Black-and-white photography, interiors, homes, the Cathedral, the prison cell, the courtroom? Musical score?

4. The title, generic, audiences linking it to the trial of Cardinal Mindzenty? His reputation, condemnation, imprisonment, the Hungarian uprising in 1956, his staying in the American Embassy, transferred to Rome? Considered a hero?

5. Alec Guinness and his performance, appearance, the background story, his work in the resistance, torture and his bearing it, resilience? His mother, memories of her, ashamed of her? Study, scholarship, his choices, the nature of his vocation, ambition, his work is a priest, as a bishop, as a Cardinal? The opening and seeing him at the Cathedral, the rituals, the congregation, the servers and attendants, the warning that the police were present? His gravitas? Allowing himself to be arrested?

6. The interrogator, his past, and the resistance, knowing the Cardinal? Patriot, a man of the party? His medical background, psychological approach, manner? Ingratiating himself, yet relentless? The various interactions and interviews? The cell, the mock court, his motives, the authorities, their critique of his method, being slow? His assistant, recording the interviews? Editing them, later playing them and the Cardinal’s wise disposing of them (along with falls maps. Information)? The jailer and his approach? The interrogator’s secretary? The plans to break the Cardinal, issues of humility and pride, in the context of his life? Yet the interrogator admitting that he was humble?

7. The jailer, the touch of comedy, his observations and comments? Treatment of his prisoner? Friendship, hostility? Later in the imprisonment, the prisoner being deprived of light, too much light, losing sense of time, the irregular bringing of the meals? The jailer recounting his experiences?

8. The assistant, subservient to the interrogator, the recordings, his editing them, shrewdness, his being exposed?

9. The secretary, his work as a party man, his being in love, the woman, her imprisoned husband, the relationship? Their meeting at the cafe, principles, abiding by them or breaking them?

10. The authority figures, their role in government, the criticisms of the interrogator, wanting things done in haste? The interviews with the interrogator?

11. The prisoner, in his cell, small, his being confined, the light, then not able to sleep with the light off? Dreams and nightmares? Discussions with the jailer? The visits of the doctor, the doctor’s embarrassment because he knew the Cardinal and his past? His verdicts? The meals, the irregularity?

12. The scenes of interrogation, the Cardinal using his wisdom, wiles, fencing verbally with the interrogator? The psychological games and interactions?

13. The interrogator bringing in the Cardinal’s mother, the threats? To go to an institution? The reality that she was already in one? The Cardinal and his being unable to touch his mother, show signs of infection, the revelation of his shame, the interrogating unearthing his past, studies, scholarship, possibilities, his choices, wanting to be a priest? His priestly ambitions? Achieving them as being Cardinal? His breaking under the threats?

14. The details of the trial, the visuals of the courtroom, the judges and the authorities, the observers, the locals, the Russian background, the police? The Cardinal standing in the middle, his dignity, answering questions, the pressure from the interrogator?

15. The beginning and the Cardinal advising people not to believe anything he said under torture? His going into the trial, admitting everything, the condemnation? The people and their veneration, his leaving the court and then making away? The frustration of the interrogator?

16. A film revealing the tensions between Western Europe, Communist East, the attitude towards the church, the show trials and the consequences?