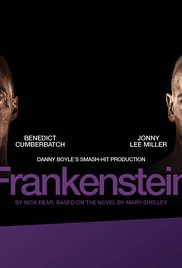

FRANKENSTEIN

UK, 2011, Colour.

Benedict Cumberbatch, Jonny Lee Miller.

National Theatre UK Live.

Directed by Danny Boyle.

During its season at the National Theatre in London, the roles of Victor Frankenstein and the Creature were performed alternately by Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller. This review is of the Cumberbatch as Creature and Miller as Frankenstein performance.

The filming of live performances from London for overseas viewing has proven a very successful program. The advantage for the cinema audience to compensate for the experience of not being actually in the theatre is that of close-ups of actors, of differing angles of photography, including overhead, making for a strong impact.

The credentials for this play are very good (as explained in a documentary preceding the screening with interviews, discussions of Mary Shelley and her work with scenes from the 1931 film version). Nick Dear has written a strongly verbal play which requires attentiveness for the richness of the themes. Danny Boyle, collaborating with cast and an arrestingly elaborate staging, has brought the 19th century into the 21st.

Benedict Cumberbatch is a somewhat gangly actor. He capitalises on this in an extraordinary opening where he mimes being born, struggling to find his feet and balance, finally being able to stand and face life. He continues this ability to present a very physical creature but one who grows in capacity for reflection, for education, for cultural awareness, for acknowledging his loneliness and his need for a bride like himself. There is a great deal of pathos in his characterisation. When all seems to go well for him and the Doctor creates a bride and then destroys it, the Creature seeks and wreaks revenge, acknowledging that he has truly become a man because he has learnt hatred, lying and shocking, violating violence. Nick Dear and Danny Boyle point out that in the Frankenstein films, the Creature does not or cannot speak. This play restores his voice.

Jonny Lee Miller comes more into his own as Frankenstein in the latter part of the play. The first half is more devoted to the Creature, his self-discovery, the friendly encounter with the Blind Hermit, the fear and loathing of ordinary people. His encounter with little William we can acknowledge as sad. But it introduces us to the proud, yet cowardly, Frankenstein, who does not know how to relate, even to his family, to his fiancée, Elizabeth (Naomie Harris), or to love anyone. He is reclusive, obsessive, arrogant in the name of science, going to Scotland and finding corpses to create the Bride, defying the Creature maliciously and returning to marry only to find that the Creature has destroyed his future. By the end of the play, the audience understands Frankenstein more but can feel little sympathy for his fate.

Ideas were important for Mary Shelley, coming into the Romantic era of the 19th century after the Enlightenment and the Age of Reason of the 18th. Can a mere human, no matter how brilliantly intelligent, have the right to create life? Is this not God’s role? And what is the result of this hubris? Only destruction. The Frankenstein story, which has become a significant myth or archetypal story, is always cautionary about the potential for science and its claims for bettering the world and the human condition (but at what physical, mental, moral and religious cost?).

All these issues are voiced in the play. In the context of the drama, they can be heard from the different points of view. Interestingly, it is Elizabeth who does not recoil in horror from the Creature but admires what her husband has achieved, but it is also she who raises the God and hubris question. They seem more important, as Nick Dear and Danny Boyle discuss in the initial documentary, because of the increasingly less presence of God in modern discourse, especially about science. Mary Shelley’s work is even more relevant in modern times.