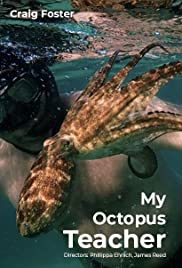

MY OCTOPUS TEACHER

South Africa, 2020, 85 minutes, Colour.

Craig Foster, Tom Foster.

Directed by Pippa Erlich, James Reed.

Within weeks of its being released on Netflix, this striking documentary was receiving high praise. For those audiences who watch the Discovery Channel and other outlets which feature nature documentaries, this one will be greatly prized. And for those who follow, and have followed for many decades, David Attenborough, this is a must.

It is a South African production. The focus is on cinematographer, Craig Foster, who, along with his brother Damon Foster, directed and photographed eight documentaries starting in 2000. Such is the attention to meticulous detail, some of the films torque several years to photograph. Foster then said he tired from the pressures of so much energy for film-making and moved away to recuperate.

However, after some years, living on the Western Cape of South Africa, he began to explore under the waters of the sometimes turbulent coastline. He took his camera and discovered a most unusual subject for his film.

Very few of us will have thought immediately of an octopus as the star of a nature film. It is not the most attractive-looking of creatures, quite primaeval in its way, eyes, body, tentacles – though it does look more streamlined as it takes off, darting and swimming through the water. Over a period of almost a year, Craig Foster went into the water, discovering a particular octopus, following the details of its life and activity, underwater close-ups. He certainly got to know the octopus and understand it – and this he shares with his audience. The film uses the interesting device of interviewing Craig Foster as a “talking head� and his narrative of his year’s activities. However, as he speaks, we watch him underwater, and not only him, the vast range of fish and sea creatures, including sharks, who inhabit this rarely seen underwater kelp forest.

The visit with the octopus become very personal, personalised, and this is true as we see how the octopus feeds on the sea depths, but it is also threatened by the shark and is ingenious in its way of defending itself (it is female and Foster continually refers to it as she and her). There is also some pathos at the end of the journey, the mating, the laying of the eggs, the end of her time.

There can be various responses to this film. First of all, of course, there is just the delight of the photography, the beauty and colour, the variety of undersea life. Then, it follows that we develop our sense of wonder, what we often call the beauty of creation, and appreciate that for the last 10 years, 100 years, 1000 years, 10,000 years and more, there has been this life, this vitality, nature evolving, all unseen by human eyes. We can be overwhelmed as we realise the range of nature on earth, under the water, and the intelligence of its evolution.

Because Craig Foster speaks very personally about his own life and career, for younger audiences watching the film, it is a challenge as they watch his achievement as to what they want to do with their lives, the call to participate in this, an enjoyable play of words on the photographer’s name, to “foster� the development of nature and, in the era of climate change, to prevent its destruction. And for those for whom this is not a career, it can be a creative hobby, a significant cause, but always the perennial hope that nature will not only survive but flourish.