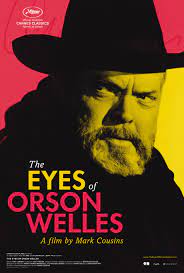

THE EYES OF ORSON WELLES

UK, 2018, 115 minutes, Colour.

Mark Cousins, Jack Kleff (voice of Orson Welles).

Directed by Mark Cousins.

Northern Ireland cinema researcher and historian, Mark Cousins, has built up a substantial body of documentary work on cinema. He now turns his attention to Orson Welles, using a very personalised approach to the life and work of the celebrated actor, director.

The first thing to note is the conversation style of the narration. It is Mark Cousins, rather softly spoken, with his distinctive accent, addressing himself to Orson Welles throughout the film, asking him questions, making observations, suggesting ideas and approaches to him.

The second thing to note is the emphasis on Orson Welles as an artist, his early training as an artist, his incessant sketches, especially in preparation for his films, design, framing… But also his delight in sketching people and places throughout his travels and career.

The film does serve also as a biography of Welles, not straightforward, although it does begin with his childhood, his parents, his travels, his training as an artist, his work in New York City around the age of 20, in radio, in theatre, and eventually moving into film. Cousins also uses the device of looking at various sequences and clips to illustrate his points, scenes which dramatise so many aspects of Welles’ life. He can be compared to Charles Foster Kane. There are many sequences, illustrating his relationship with the Rita Haworth, from The Lady from Shanghai.

The film does trace his marriages and relationships, with a great deal of commentary and presence from his daughter, Beatrice and his archives. But there is also his love for travel, for people, and seeing him both from aspects of Knight and Jester.

We see you Welles’ great love for Shakespeare, his interpretation of Macbeth, his dark presentation of Othello, his familiarity with the inn, The Boar’s Head, the rousing Falstaff, and the pathos of his rejection by Prince Hal and Chimes of Midnight. There are also glimpses of a short film, not completed, about Don Quixote. And Cousins has an admiration for Mr Arkardin and for A Touch of Evil. There is not so much attention to his later work.

Rather, Cousins relies, most interestingly, on clips from interviews that Welles did, especially during the 1960s, his whimsical tone, his serious themes, his philosophical reflections, his political stances.

And, all the time, there is the emphasis on Welles’ eyes, what he saw, what he sketched, how he interpreted what he sketched.

(Some critics are very negative towards Cousins’ device of the interview and dialogue, dismissing it as pretentious and focusing on Cousins himself; and, possibly, Americans, highly critical of an Irish accent commenting on their American actor dismiss his tone and his range of questions and observations. Those who appreciate the style and Cousins’ personalised voice and treatment, will find this documentary highly illuminating.)