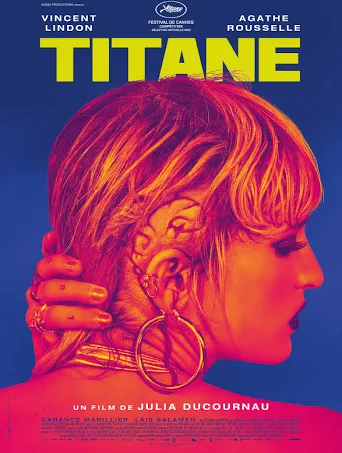

France, 2021, 107 minutes, Colour.

Vincent Linden, Agatha Rousselle.

Directed by Julia Ducornau.

Winner of the Palme D’Or at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. Not without comment and controversy.

With controversial films, there is sometimes a focus on brief sequences, unexpected, even shocking, that command headlines, criticisms, even fears for those who have not seen the film. And this is the case with Tatine. Yes, there is a graphic sequence of sexual fetishism, the central character, Alexia, and cars, with the consequence, controversial, of her becoming pregnant.

But, there is much more to the film than that, not found generally in the controversy discussions.

It is true that the director, Julia Ducornau, has shown a quite idiosyncratically curious attitude towards aberrant human behaviour, violence and cannibalism in her first film, Raw, and now the strange adventures and misadventures of Alexia.

The film is very stylish, visually, pace and editing, colour design – on the technical side, very striking. But, while it invites the audience to appreciate the narrative as realistic, it is clearly not. We are in the area of metaphor, of symbols. And we are in the realm of the bizarre, sometimes weird.

The tone is immediate with a father driving his young daughter, her moodiness, kicking the back of his driver’s seat, a swerve, a crash, her going to hospital, injuries to her head, the insertion of a titanium plate – titanium/titane. The little girl shows an attraction to and attachment to the car. And the transition to an elaborate car exhibition sale, highly sexualised, models cavorting on the cars more than provocatively, the guards warding off lewd males, urging no touching, only looking – which puts us in their position so that for the rest of the film, we are compelled to be voyeurs (or we could leave the cinema). And there is a great deal to be voyeur about.

Very quickly, we discover that Alexia is, in fact, a serial killer – and some grim close-ups of her attack on an overeager fan, a lesbian fellow-model, a group in a mansion for a sex weekend. Posters of her, wanted by the police. But, that is not how the rest of the film goes. There have been TV news episodes, posters, about the disappearance of a boy and the parents seeking him back. And this is where Alexia decides to hide, encountering the missing boy’s father, played by screen veteran, Vincent Lindon, who works with the local fire brigade (and is offering quite a nuanced performance of a grieving man, an obsessed man, a puzzled man), welcomes Alexia to his home, to his workplace and colleagues, providing a refuge for her and she disguises herself. And, of course, she is pregnant, the bizarre pregnancy being noted that instead of blood flow, she has black classic gasoline flow.

Titane is in no way predictable in the unfolding of its narrative. If this review has proved intriguing, there is certainly more to be intrigued by.

The director is certainly wanting her audience to do a great deal of thinking about the themes that she is dramatising, identity, sexuality, male-female relationships, male exploitation often crass attitudes towards women, mental conditions, propensity for violence and killing, sympathy towards the killer or not… But, because this is a visual experience, the audience is feeling these themes rather than analysing. Which makes the film often uncomfortable viewing, often bewildering viewing, emotionally testing viewing. No conclusions except an affirmation of love and relationships. Which, it would seem, is the intention of the director.