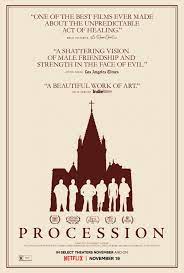

PROCESSION

US, 2021, 116 minutes, Colour.

Directed by Robert Greene.

At first, the title seems to suggest liturgical processions (and there are some re-and acted in this documentary) but the title is linked to Process, Processes, and, in this case, to clerical sexual abuse cases.

Over the years there have been many films (features and documentaries) dealing with the realities of abuse church-wide. (For an overview, see the chapter in Screen Priests by this author.) These films are not comfortable viewing and many audiences have chosen not to watch. But, whether we watch or not, we know we have to face the realities. This is especially the case for empathy with the abused, especially underage boys and girls, the prey of paedophiles.

This is very important for Procession, especially as it has been available for worldwide viewing since November 2021 on Netflix.

Many who do not share Christian faith will be appalled. And Christians too. It can be said we need to be appalled. I have watched Procession twice. Once where the impact was overwhelming. A second time to try to appreciate more realistically and sympathetically the real stories of the six American men, their experiences of abuse in Kansas City, Missouri and Cheyenne, Wyoming, and not just read their stories but listen to their voices, tones, emotions, bewilderment, hesitations, rage, and their lifelong regrets at their loss of innocence so young and their being dominated by clerics who claim to be men of God.

And, the great advantage of the film is that we can see and response to body language: faces, passive and impassive, frowns, smiles, pauses, bloated comments, outbursts seen in the body and not just heard in words.

One of my regrets is that the South African model of the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation was not a feature of the church’s experience of ministry to the abused (and pastoral care for the abusers). Instead, the approach taken has been legal, concerned with finance and compensation, adversarial (despite the principles of Towards Healing). An adversarial model, court cases and prosecutions, settlements, has taken predominance.

In more recent decades, in connection with assault cases, injury, burglary and theft, methods of Retributive Justice have been encouraged, assailants and those attacked meeting for some meeting of minds with a facilitator.

However, Procession takes a different approach, an innovative approach: drama, re-enactments. The film’s director, Robert Greene, saw a press conference on television with four of the men with their lawyer, Kansas City prosecutor for many years, Rebecca Randles, with her assistant.

Greene had the idea for the men to meet, share their experiences, regrets, rage, frustrations and then for them to work together, write brief screenplays – and perform them. A risky project. However they employed a skilled drama coach, Monica Phinney who is present for all the discussions and filming.

Over the running time of almost 2 hours, we get to know the men very well. Ed, marriage, eager to explain his situation to his daughter. The angry Mike, never having an intimate relationship, unmarried, still enraged, swearing, condemning the willingness of the Archbishop of Kansas City and the independent tribunal to give credence to his stories.

There is the large 62-year-old Tom, case still pending, who volunteers to role-play bishops and priests and baptisms, the confessional and standover commands to the boys. Joe is more quiet, tormented by nightmares, trying to rediscover his child-self, an interior grief. Dennis’ memories have surfaced, his older brother also being abused, and filmed excerpts of conversations now with his mother. Finally, there is Mike Sandridge, quiet, devout, intense, a listener, an actor, but also working with others on their screenplays. The films we see have evocative titles: Altered Boys, Confessional, Blatant Lies in the Name of the Lord, God Switches Sides, Letter to Joe, some of them are emotionally intense, the men reliving those experiences.

Part of the men’s therapies consists of visits locations, churches, holiday camps, and reconstructing sets in churches and a studio.

Offending priests (and a Bishop) are named and photos shown. The credits show help from Catholic offices in Kansas City and Cheyenne and participation of the current local Bishop. Most of the cases are still pending.

A young boy Terrick has agreed to appear in each of the films, under the care of his parents and the concern of the men that Terrick not be traumatised by the films – and care in debriefing him after the episodes.

There is a rueful comment as Ed writes to Pope Francis and is happy to receive a personal reply. But his abusers have not yet been condemned. And he says that perhaps the Pope didn’t have quite the clout he thought he had.

One hopes that Procession and its being seen widely on Netflix will move cases on and help the church to develop more clout in both compassion and justice.