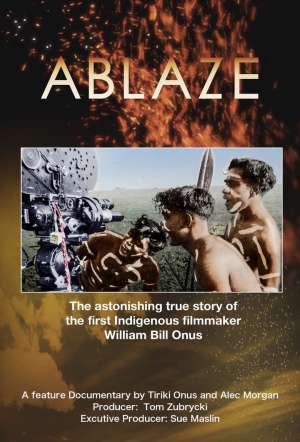

ABLAZE

Australia, 2021, 81 minutes, Colour.

Directed by Alec Morgan and Tiriki Onus.

Very glad to have seen this striking and interesting documentary introducing a highly significant First Nations advocate for rights from the 1930s to the 1960s, Bill Onus, a Yorta Yorta and Wiradjuri man from Victoria, dying soon after the 1967 referendum. The film is directed by Alec Morgan who, almost 40 years ago directed Lousy Little Sixpence, a documentary about the stolen generation. His co-director and narrator of the film is the opera singer, Tiriki Onus, the grandson of Bill Onus (and sings the role of his grandfather in Deborah Cheetham’s opera, Pecan Summer, an excerpt included in this film).

Three reasons for recommending this documentary.

The first is its representation of indigenous Australians in film footage from the 1930s and 1940s, found in the National Film Archive in Canberra, film shot by Bill Onus, who had his own camera, and also took many photos. His grandson finding a lot of this material in a suitcase in an attic. Quite some archival treasures found in it. And we have the opportunity to see this material, especially as Tiriki Onus shows it to a wide range of people for their comment, archivists, historians, World War II experts, Uncle Charles, family members, neighbours from Fitzroy. There is identification of where some of the material shot, especially when Bill Onus lived in Fitzroy, but capturing images of aboriginal soldiers, many of whom spent years in prison on the Burma Railway, and what happened after their return – and lack of recognition.

Bill Onus was very concerned about social issues over these decades, speaking at every opportunity, travelling, filming and dramatising in a filmed play the first aboriginal strike in 1946 in the Pilbara – and Titiki returning to show them the film. Interestingly, the film highlights how Bill Onus may have been the first indigenous cinematographer, working with Charles Chauvel in the 1930s on Uncivilised, British director, Harry Watt, getting his advice for the classic, The Overlanders, trying to find ways of public exhibition of his films, in later years having a television program, telling aboriginal stories to camera.

The second reason for recommendation is for non-indigenous Australians to learn more about the history of the aboriginal peoples, the invasion/colonialisation of Australia, some appalling examples of white superiority, segregation behaviour, some slavery and punishments, the challenges by Bill Onus, supported by his Communist Party wife and her fiery enthusiasm. There is a great deal of material here for contemporary Australians to examine the consciences of the past, confess to these abuses and find ways to make atonement, for restorative justice.

The third reason for recommendation is the archival work. Archives need to be established, to be cared for, to be made available for the kind of research that results in this film. It is exciting for researchers to make personal contacts, for interviews, for identification of characters within the film is (as happens here with the most decorated of the aboriginal soldiers as a tram conductor in Melbourne after the war, in becoming more involved in justice campaigning), for finding the clues, like him into finding buildings in Fitzroy, that helped to re-create the look, the sound, the realities of the past. (This particularly appeals to this reviewer, long involved in research, an example from this film is seeing the movie posters, especially for The Hard Way in the post-war tram (released in 1943 in the US), and the cinema screening My Man Godfrey, 1936.)

Titiki Onus is an engaging personality, friendly, earnest in his research, making every effort to show the film to a range of people, get their advice, but provide a rounded portrait of his grandfather and a tribute to his energy and achievement.