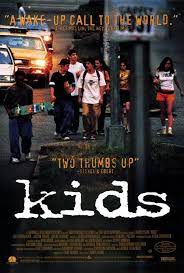

KIDS

US, 1995, 95 minutes, Colour.

Leo Fitzpatrick, Justin Pierce, Chloe Sevigny, Rosario Dawson, Harold Hunter, Hamilton Harris, Harmony Korine, Peter Bici, Jon Abrahams.

Directed by Larry Clark.

Kids is a small-budget feature, written and directed by Larry Clark. It has been much argued about. There has been some controversy in the US and the UK as to whether it should be banned or not. With the 26th December release of the film around Australia (a time when there is very little political news because of the beginning of the summer holidays), the media has reported on the film's controversial subject and style.

Many audiences have found it too confronting with its picture of New York lower middle-class teenagers who lack any moral sense and who are enmeshed in the drug culture and whose ambitions peak at irresponsible and self-gratifying sex.

At a Melbourne preview some social workers stated that these kids were exactly like some at our own remand centres. It is easy to be horrified and denounce Kids. But, we cannot gloss over the more desperate sides of our society and the efforts of so many to reach out in generous and often seemingly fruitless help.

The complex world we live in and the moral questions that are raised are often well dramatised in films. While films are generally seen as entertainment of the relaxing kind, they have a strong place in mirroring our world and offering us an entertainment that also educates.

Many older audiences (and some young ones) were brought up in a religious world where it was thought everybody should behave practically perfectly and we set ourselves ideal standards. We were very disedified when these were not put into practice, but we were protected, in those days, from a world that was frequently amoral. And many of us have come to expect that films should portray an edifying world and are often wary of stories that present us with characters who do not share our values.

But our Christian discipleship and our concern for all and, especially, those who are oppressed in any way should take us into an experience of the arts that shows us this world and these characters, shows us the struggles and the searches, shows us the ugliness and the sin so that we appreciate the profound sadness and despair, the temptations, falls. We need delicate but robust sensitivity.

While the treatment is graphic (more verbal than visual) and the behaviour of the teenagers will shock many audiences, the film reflects a part of today's society and its moral problems and makes a plea for change (especially to parents).

In the U.S. where the ratings are based on a voluntary code, Kids did not receive a rating (thus avoiding the NC which requires anyone under 17 to see the film in the company of an adult) and was left to the discretion of the cinema managers.

The film has received an R 18+ classification in Australia. This means that those under 18 are not admitted by law. It might have been more helpful had the film been available to teenagers with adults who might then discuss the issues. An MA 15+ classification would have enabled this as it allows those under 15 to see the film in the company of an adult.

1995 and controversy, some personal background.

The press release for Kids was the first of my press releases, issued as 'A Statement from the Australian Catholic Film Office'. A reporter for the Melbourne Sun had made contact with a number of Christian offices, inviting representatives to a preview screening of Kids. Its director, Larry Clark, a photographer, allegedly had a history of drugs. His film was about kids in the New York streets indulging in drugs and sex, running the risk of HIV infection.

At the discussion after the screening, it appeared that all the Church people the journalist had invited were not going to condemn the film at all. Instead, a number of pastoral care and social workers who belonged to more evangelical churches,

especially the Baptists, while not enjoying the film, said that it was a fair representation of what they found amongst some kids on the streets of Melbourne. The journalist was not impressed, left in a huff and no article ever appeared.

In the meantime, the Melboure Age asked the Communications Office for a comment. It was the week before Christmas with Kids due to be released on Boxing Day. A bit of a slow week for stories, but someone had heard of the preview we attended.

I wrote the following statement. The Age headed the report, 'Support for Kids from unexpected source' (or words to that effect) stating that the Catholic church had lent its support to Kids. That was not exactly the case! The Age journalist faxed through the article and changed a couple of things at my suggestion. (I have found when journalists realise you know what you are talking about, they pay attention.)

The ABCs 7.30 report had some footage of interviews with Larry Clark when he had promoted the film some weeks earlier. They had a brainwave to make a seven minute feature, going to cinemas to ask patrons, especially the young, whether they liked it or not. The interviewees tended not to have liked it. There were bits of Larry Clark. And some fair bits of me sitting at home trying to say that these were issues we had to face whether we liked it or not but that not everybody needed to see this particular version of kids and drugs.

As always, I sent my releases to Brussels. Guido Convents printed it early in 1996. It was the period of the centenary of cinema and the publication of the list of movies recommended by the Pontifical Council for Social Communciations (and, therefore, according to journalists, by the Pope).

The British Film Institute's magazine, Sight and Sound, published an editorial on Church interest in cinema. The editorial was initially taking a shot at the doyen of British reviewers, author Alexander Walker, of the Evening Standard (though they did not mention him and his condemnatory remarks about Kids by name). The editorial then went on to praise the Catholic Church and its stances. At the same time, Derek Malcolm, veteran reviewer for The Guardian, asked about ten representatives of the churches in England for their lists of excellent films to compare them with those from the Vatican. He was impressed by the Catholic list - enough to make one seriously think of becoming a Catholic!

However, the Sight and Sound editorial, 'Fallible Judgments', included these paragraphs.

Kids has prompted this moral controversy partly by raising the troubling issue of adolescent sex, something society's Moral Guardians, especially the Church, have traditionally felt the need to deplore. So it is ironic that certain elements in the Catholic Church are demonstrating a far more generosity towards Kids than these secular commentators. In a forthcoming issue of Cine & Media, published by OCIC (Organisation Catholique Internationale du Cinema et de l'Audiovisuel), Father Peter Malone writes in Kids' defence, noting that 'while the treatment is graphic (more verbal than visual) and the behaviour of the teenagers will shock many audiences, the film reflects a part of today's society and its moreal problems and makes a plea for change (especially to parents).'

The editorial then refers to the Vatican's 100 films for the centenary of cinema and (rightly) notes that the list did not come from the Pope but from Msgr Enrique Planas in a booklet distributed to Italian schools to encourage media literacy.

Then another mention:

Nevertheless the Pontifical rubber stamp indicates (in the words of the Catholic Herald) that 'the Vatican is now acknowledging the beneficial effect that films can have on the lives of their audiences,' a view already endorsed by such open-minded clerics as Father Malone. This is in marked contrast to the Christian fundamentalist groups in the United States who have lobbied against films deemed offensive to their principles. One group even runs a hotline which anxious filmgoers can ring and find out how much swearing, violence or sex a particular film contains. Kids was a notable recent target of these groups...

As the abuse of Kids gathers momentum over the next few weeks, it will be interesting to see whether British religious groups jump on the banning bandwagon or show the intelligence of their Catholic brothers and sisters.

Alexander Walker was not impressed by their treatment of him, "even trimming a film like Kids in order to sanitise a censor's conscience and make possible a distributor's profit cannot remove the way in which almost the whole emphasis of interest is placed on apparent minors aping the lasciviousness and debauchery of adults". The editorial did not refer to him by name, mentioning only The Evening Standard. He immediately penned a reply. Sight and Sound headed it 'Ego te absolve'.

Your editoritorial (S&S April) gives a source for the adverse quotation you use (Evening Standard) but names no author for it. This is sloppy journalism and, since the passing of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, an unlawful denial of the writer's right to be named when his or her work is being cited in a text. In the film's defence you quote (and this time name) one Father Malone. You clearly place great faith in the heterodoxy of Roman Catholic clerics. You will therefore understand my surpirse at the anathema my own name continues to cause you when you quote from my writings - as you again did several issues ago - without any authorial attribution. I suggest you discontinue this practice, lest it blind you to the requirements of scholarly discussion, and I shall absolve you from this sin of omission, imnposing on you only the penance of three Hail Mary's to be said on your knees when reading the review of kids which, deo volente, shall appear in the Evening Standard when the film opens.

So, for the fun of it, a letter to the editor.

20 July 1996

Dear Editor,

I thought I would make myself known after reading your kind words in the editorial of April on the Catholic Church's approach to films and your quoting me about Kids. My June copy of Sight and Sound has just arrived and I see a rather detrimental comment about heterodox clerics from Alexander Walker - so I thought I would send you a `Letter to the Editor'.

In fact, I am the director of the Australian Catholic Film Office for the Bishops of Australia as well as the President of the Catholic Film Offices of the Pacific and a member of the International Board of Directors of O.C.I.C. (International Catholic Organization for Cinema and Audio-Visuals). So, `heterodox' sounds somewhat over the top. But before that I have been a regular reviewer of films since 1968 in religious publications as well as newspapers and Cinema Papers and written a number of books. In fact, in the post yesterday was an invitation to write the entry on `Religion' for The Oxford Companion to Australian Film.

I have appreciated The Monthly Film Bulletin and, now, Sight and Sound for my work.

Sincerely,

I had the opportunity to go to the Venice Film Festival a month later and wondered whether I would meet Mr Walker. David Stratton of SBS and The Australian mentioned that he had seen the letter - and added that Alexander Walker was not attending the festival as he had had a car accident, knocked down by a taxi!

On moving to England in 1999, I made myself known to him and he wished me well in my work.

______________________________________________

THE KIDS/WE WERE ONCE KIDS

Australia, 2021, 88 minutes, Colour.

Hamilton Harris, Jon Abrahams, Peter Bici.

Directed by Eddie Martin.

In 1995, an unusual drama featuring teenagers, Kids, was a sensation, winning awards and critical acclaim, but a source of contradiction for many groups, social workers, religious concerns. It became a commercial success, talked about, seen by large audiences, discussions, media programs.

Australian documentary director, Eddie Martin (films about skateboarders, street artists, the 2019-2020 bushfires) takes the audience back 26 years but also offers a perspective on the film and the atmosphere of the 1990s, especially in a neighbourhood in New York City.

The film has a great deal of archival footage from the period. Which means that an audience who has not seen the original Kids gets a fair and strong impression of what the film was about, its dramatic cinema style, the issues of the period. There are various footage interviews with film critics such as Roger Ebert who was strongly in favour. There is footage of the director, Larry Clark, a noted photographer who made a number of further films, not without controversy. The writer of the film, Harmony Korine, 19 at the time and from the neighbourhood, is glimpsed in the footage from the past. Clark and Korine declined to be interviewed for this documentary.

In the present, there is continued interview and narrative from one of the teenage stars of the original film, Hamilton Harris. He is co-producer of the film, wanting to have his say and perspective about what it was like to make the film, and the contact with fellow actors, especially Justin Pierce (who won some awards for his performance) and Harold Hunter. There is extensive footage of each of these young men, during the making, the aftermath, ambitions careers, success, death and suicides.

One criticism of this documentary is that the prominent stars, Rosario Dawson, Chloe Sevigny, Leo Fitzpatrick, were not interviewed (a glimpse or two of Rosario Dawson in past footage). The comment is made by the locals that the film was mainly about those who lived in the neighbourhood, amateurs, whereas the three stars were brought in from the outside, not part of the daily life dramatised in the film.

The picture of teenagers in New York is frank, the role of drugs and alcohol, sexual relationships, in the background of some poverty and lack of education. The invitation to become part of a feature film was attractive to these young people. Some money. There was criticism of the time and certainly afterwards that the filmmakers were exploiting them. With the footage and the contemporary interviews (especially by other stars of Kids who have survived and had careers, Jon Abrahams, Peter Bici, reminiscing about their lives, the film, the making, and the relationships with Pierce and Hunter).

There is a surprising discovery at the end of the film, an Australian who, after a long time, discovers that he is the father of Justin Pierce.

This documentary suggests that audiences might well go back to see Kids again or for the first time, comparing the picture of life in the neighbourhood in the 1990s with pictures of life there in succeeding decades. How much change, or not? And the same issues for teenagers and challenges?

One of the strong criticisms of the film at the time was: where the parents? They are notably absent in the original film – and the question of what life would be like for those participating if there had been some kind of adult guidance and/or control.

This is an interesting social documentary. It is also a must for those who love the movies and are intrigued by the backgrounds.