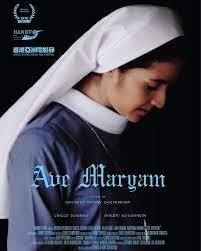

AVE MARYAM

Indonesia, 2018, 85 minutes (Netflix 74 minutes), colour.

Maudy Koesnaedi, Chicco Jerikho, Tutie Kirana, Joko Anwar.

Directed by Razka Robby Ertanto.

World audiences do not see many films from Indonesia. Some of the action shows do get release. However, this film of 2018 was released directly to Netflix and so available worldwide.

This is a very Catholic-themed film. And this is significant in Indonesia as one of the world’s largest Muslim populations. The film is an assertion that there are other religious beliefs in the country – and, interestingly, the actress Maud Koesnaedi who plays Sister Maryam so convincingly, is herself Muslim.

The setting is 1980, a time when Hollywood was making a number of films about priests falling in love, relationships with nuns, nuns leaving the convent (Broken Vows, The Thorn Birds). To that extent, it parallels these films.

A great deal of attention has been given to the Catholic setting, scenes in the church, scenes of the sisters at mass, their prayer, the relationship with the priest who is chaplain, the young priest with his more “modern” styles, the choir, clerical dress, ordinary dress, familiarity with people. The screenplay gives a great deal of attention to the life of the nuns, the more adapted religious habit of 1980, community life, prayer, the meals, kitchen, work in the laundry, sewing, and the care for the elderly sisters. The film offers a good impression of convent life. Choir sings familiar Christmas songs as well as the him, How Great Thou Art.)

The focus is on Sister Maryam, who celebrates her 40th birthday during the film. Which means that she has been several decades in the convent, devoted, taking her place in the convent duties, but especially a concern for an elderly sister who needs washing, reminders of her medication, who has lapses of memory but is also very observant and shrewd.

When the young priest arrives, especially to conduct the choir for a Christmas performance, he seems like something of a breath of fresh new air. And is comfortable moving around the convent. And, especially, since he comes from this town, he pays special attention to the elderly sister.

From the point of view of the wider audience and, perhaps, the filmmakers, this is a story about a priest and a nun falling in love, their behaviour, the consequences for each of them, especially of the sister because of the title of the film, her life, her not realising some dissatisfactions, the gradual attraction to the priest, his insinuating himself, their meetings, his invitation to go out, her changing into ordinary dress, the meetings, the restaurant, the effect?

The Netflix version is 12 minutes shorter than the original version and it is easy to see where the cut took place, at the beach, the nun beginning to unbutton her dress, not an edit but an abrupt cut, leading to the imagination about what might have happened on the beach. The cut then makes a transition to the aftermath, driving home, the priest offering her a cake for her birthday, and then her late arrival, the sisters all gathering with their cake, singing, a greeting and kissing, her breaking down.

The elderly sister has observed what is going on and makes comments about conscience and commitment.

The sisters are very supportive of Sister Maryam, especially the superior who speaks to her calmly about love, the heart, vocation. There is a sadness when Maryam packs, leaves, goes to the railway station, is in the train, sees the priest on the platform, exits the train only to find he is not there.

The key sequence is her going to the church, to the confessional, not knowing that the priest is actually hearing the confessions. She makes a full confession, blaming herself, sad. The audience sees the priest also weeping as he gives her some kind of absolution.

Where is the Sister to go? Her life? What will happen to the priest?

For many Catholic audiences, the confessional sequence will be a challenge. Given the insights into clerical abuse in more recent decades, exercise of power and control, sexual domination, the behaviour of the priest here could be considered as grooming, his gradual attentions to the sister, preparing her for the seduction. The screenplay offers no blame for him for this grooming. Which means then that his weeping and the confessional seems false, not exactly a repentance but the breaking of the relationship, certainly a sadness, but his behaviour has been selfish and self-centred.

Audiences may be familiar with these themes from English-language films so it is interesting to make comparisons through an Indonesian story.