The Spanish Flu – and the Making of a True Hero.

A Catholic issue, anointing. An OLSH Randwick connection.

In our pandemic 2020, we go back to the experiences of the Spanish Flu a century ago. With thanks to the editors OLSH Randwick Bulletin.

The Spanish Flu, known as the Great 1919 Flu, saw thousands of returning World War 1 soldiers confined to the North Head Quarantine Station. And it was there that Annie Egan was to become a national hero.

Annie Egan was born in 1891 in Gundagai, New South Wales, the fifth daughter of nine children, two boys and seven girls, three eldest of whom became Sisters of Mercy. Annie went to school at St Mary’s College Gunnedah and began training as a nurse at St Vincent’s Hospital in 1915.

In the dying days of the war troops ships began returning to Sydney and bringing with them the dreaded Spanish Flu. Hundreds of infected soldiers were placed in the Quarantine Station at North Head and it was there that Annie, having passed her Nurses examination in 1918 volunteered to become a Military Nurse. She was soon to contract the dreaded flu and within months she was to die.

And it was with her death that she was to become a hero in circumstances of a bitter sectarian war and clashes with Commonwealth authorities.

The circumstances? There had been a number of priests stationed at the Quarantine Station but over time their numbers had dwindled and when Annie became ill there were none there. No replacements were allowed despite pleas to various Commonwealth Authorities by the Archbishop of Sydney, Michael Kelly.

And by late November 1918 Annie, then with the effects of the disease, realised that death was imminent and requested that a priest hear her confession and administer her the Last Rites. The Government denied her request. A local priest at Manly had offered to visit Annie but that request too was denied. Archbishop Kelly threatened to enter the Station but that request too was denied.

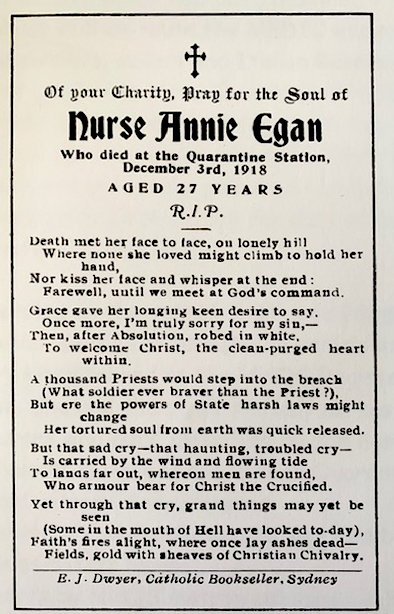

Annie died on 3 December 1918. A wave of protests followed Annie’s death, not just from Catholics but from citizens generally aghast at the denial to Annie of her request for the Last Rites.

At the Requiem Mass on 6 December with her grief-stricken parents in attendance at St Mary’s Cathedral, the Archbishop berated authorities and said ‘Let it be remembered that Nurse Egan has won the martyr's crown. They have given her military honours at her funeral. As if she had no soul. As if that were enough. They might lay a Victoria Cross or any other decoration upon her tomb, but they nevertheless denied her dying wish to have her God in the Holy Viaticum.

Fr John O’Gorman, Administrator, St Mary’s Cathedral wrote to Annie’s mother following the funeral to say Though your daughter has lost her life you should feel very proud of her bravery and fidelity. She died with prayers on her lips and sorrow and love in her heart. But besides her death awoke Australia to the consciousness of Pagan officialdom and given it a blow from which it will not soon recover. Her death in such (circumstances/ certainly) will make for religious liberty in quarters where it is more needed than people think.

AND THERE IS AN OLSH RANDWICK CONNECTION both past and present. Bill and Noeline Egan were long time parishioners of OLSH and St Margaret Mary’s who passed away in 2007 and 2008. Some older parishioners may recall them and may even know that Annie was Bill’s Aunt. And Bill’s daughter Catherine and her husband Martin Hoe and children Alison and Jennifer are members of a number of our parish choirs. Importantly the family have a treasure trove of letters written about her on her death.

From her friend Lauren writing to Annie’s sister Kate after her funeral (Annie was also known as Burns – her mother’s maiden name)

The Italians had made a huge harp about 5ft high with wild flowers which they gathered themselves & two of them carried it behind the gun-carriage all the way up to the cemetery. It was so good of them and they had Annie’s name in flannel daisies in the centre and the Italian flag at the head. Everyone here loved Burns – the men were continually asking about her and they all said how cheerful and bright she was and so willing. She has left a wonderful record dear and will never be forgotten. The cemetery is right on the point of the Head and overlooks the Harbour to the ocean outside.

From Fr Daniel Keane the Parish Priest of St Joseph’s Church Gunnedah

Now whenever any difficulties are placed between the sick and their priests, Remember Nurse Egan! Her name resounds through the whole country as a synonym of deep, sincere, religious and patriotic culture. We continually hear people parading their patriotism for their own private ends. But her action has given a noble lead in this virtue, so much extolled in people but so little practised.

And the story recounted by Lil, Annie’s sister, about a young soldier who approached Annie’s brother Matt (Catherine’s Grandfather) at Central Station as he was returning by train to Gunnedah. The soldier asked if he were Nurse Egan’s brother and immediately shook his hand and apologised, stating that he had been guarding the gate at the Quarantine Station and was very sorry as he had orders not to allow anyone in. That anyone included Archbishop Kelly.

Eight days after Annie’s death and with pressure mounting to change its stance on refusing priests access to the Station, the government agreed to allowing chaplains access to the Station.

In honour of Annie Egan a Memorial Headstone was erected at the Quarantine Station.

References: Egan family; Jeff Kildea -The Australasian Catholic Record; Croppies Downunder. Samantha Elley- Tales from the Grave. Various Trove articles