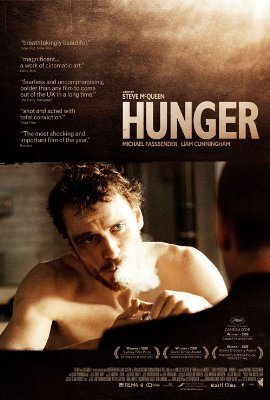

HUNGER

UK/Ireland, 2008, 96 minutes, Colour.

Michael Fassbender, Liam Cunningham, Stuart Graham.

Directed by Steve Mc Queen.

A gruelling film to watch (and feel).Turner Prize-winning artist, Steve Mc Queen, has co-written and directed his first feature and drawn his audience into the Troubles of 1981 in Belfast, especially in the Maze prison at the time of the blanket and washing strike, culminating in the hunger strike and the death of activist, Bobby Sands.

The film is clearly divided into three parts. The first hour focuses on the inmates and the conditions in the Maze and their demands to be treated as political prisoners because of the IRA war rather than as criminal murderers, a plea turned down by Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, whose severe (and arrogant-sounding) words are played here.

One of the difficulties of any armed movement against a government is that, depending on where sympathies lie, participants are lauded as resistance fighters (World War II France or the opposition in Mugabe’s Zimbabwe or Begin’s Jewish fighters against the British before 1948) or condemned as terrorists (Palestinians, Tamil Tigers and any number of groups since September 11th 2001). Northern Ireand was a hotbed of terrorism and counter-terrorism by local militias – and with occupying British forces present to keep order. As this film indicates more than 2000 people were killed between 1969 and 1981.

There have been many notorious prisons. In recent times we have seen the atrocities at Abu Ghraib in Bagdad and there have been the controversies about Guantanamo Bay. Governments have been stepping up security and detention legislation. But, before that, there was the Maze.

Wise commentators have stated that one can determine the civilisation of a nation by the way it treats its prisoners. Conditions shown in Hunger are appalling: men stripped, clad in blankets (since they refused to wear criminal garb), isolated in cold cells which they have smeared with excrement in protest. The men have to wash and dress to see their visitors (where a whole lot of smuggling letters and radios goes on). Beating and kicking are rife – and we are not spared any of this detail in the film. The riot squad as well as local guards exercise a shameful brutality – which makes us wonder throughout the film where these people came from, what they were like in real life with their families. Hunger brings this home to us as it opens with a local guard having his breakfast fry, checking the roads and under his car before he goes to work. He laughs with his mates – but then he shows a brutal side with his bloodied knuckles. And anonymous killers eventually execute him as he visits his mother in a nursing home.

The second part of the film is an intense conversation between Bobby Sands and his friend Fr Dominic Moran. Much of it is in a single take, a medium shot as the two men sit at a table and argue the pros and cons of Sands’ decision to go on a hunger strike to death. This demands constant attention as the different points of view are persuasively put. Is Sands too much of an idealist, wanting to suffer, to be a martyr, expecting that history will remember him (which it does)? Should he have a broader view and be open to dialogue and negotiation so that life will be respected? This is a long sequence well performed by Michael Fassbender as Sands and Liam Cunningham as Fr Moran. Interesting to see the Catholic background of the men (although in a Eucharist sequence, the priest is frustrated as the men chat loudly over his reading of a psalm and catch up).

Before the third part there is another long single take as a cleaner mops up the urine that the men have tipped under their doors into the corridor. This gives us time to absorb some of the conversation we have listened to.

Then there is the 66 days of dying that Bobby Sands underwent, with explanations of what the hunger did to his internal organs. We can see what it was doing to his exterior, with Michael Fassbender looking frighteningly emaciated, dying with pain and an attempt at dignity.

Hunger joins a number of films about this era including In the Name of the Father and Some Mother’s Son (which was about Bobby Sands, his hunger strike and his being elected an MP during this time, something Hunger mentions only in the end information). The IRA committed atrocities. The British and the prison guards do themselves little credit in their behaviour. It is more than a blessing that matters have been able to change in Northern Ireland since the Good Friday agreement of 1997.

1.The impact of the film? Its acclaim? The experience of The Maze prison? The IRA prisoners and their conditions? The Irish background, the Troubles, the terror? The IRA seeing this as a war against England? The political background – and Bobby Sands’ election to parliament after his death?

2.The introduction: 1969-81, the rights and wrongs, the context for the hunger strike, the IRA terror, the response of the Protestant forces? The prison?

3.The structure of the film in three parts: prison, the talk with Father Moran, Sands’ death? The overall impact of these three acts and their interconnectedness?

4.The introduction, Raymond Lohan, his ordinary home life, his family, breakfast, checking the streets for security, washing, his jokes? The inscription on his knuckles? The contrast with seeing him at the prison, changing, the other guards, his brutality and torture? His visiting his mother – the ordinariness? His death?

5.The portrait of the guards, the recruits, their violence and brutality, the motivations? The stripping of the prisoners, the search, the beatings? The response to riots? The hostility – and the man weeping?

6.Dave Gillon and his arrival, the declaration, stripped, the blanket, the cell, his companion in the cell, Campbell? Life in The Maze, loneliness, solitude? Going out and brutality? The meals? The excrement on the walls? The messages, concealing them? The exchange of visits? The aftermath?

7.The visuals of the cells, the filth, painting, hosing, urinating in the corridor?

8.The sequences with Margaret Thatcher, her attitude towards Ireland, the Troubles, the prisoners, The Maze? Her finally changing some aspects – but not her policies?

9.The riot squad, the noise, the brutal beatings – and the shootings?

10.The film’s portrait of Bobby Sands: in himself, his action as an IRA gunman, the bank robberies? His personality? His leadership in The Maze? The attitude of the authorities, the guards? Visits, his parents? The importance of the conversation with Dominic Moran? Its length? The single take at the table? The background of talking, clerical etiquette, smoking, exchanging stories, Sands’ brother, the parish priest? Hard work, the seminary, homilies? The priest and negotiations? Life and values? Out of touch? The issue of hunger strike, suicide? Jesus’ death, the martyrs? Sands and his righteousness? Being challenged by Father Moran? Sands and his ego in his stance? Beliefs, convictions? His death? The overall impact of the conversation?

11.The long corridor, the mopping?

12.Bobby Sands and the hunger strike, thin, ill, his body? The sores? The treatment? The role of the doctor? Not eating meals? The examinations, the bath? His collapse? The visit of his parents, conversation with them? His death? The importance of the flashbacks, Sands as a boy, his joy, in the forest, the foal, putting it to death? Belfast, the running?

13.The images of forests and birds?

14.The reality of Bobby Sands’ hunger strike, the sixty-six days?

15.The aftermath, his being elected as an MP, the role of the government?

16.The director, how objective his presentation of both aspects of the Troubles? Sympathy towards Bobby Sands? Making him a martyr? The critique of Sands? The critique of the IRA and their activities – and the various victims of their brutality? A film inviting audiences to reflect on a more immediate past?