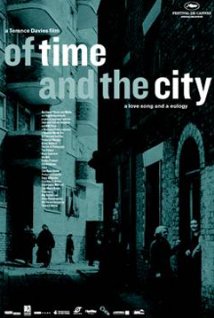

OF TIME AND THE CITY

UK, 2008, 74 minutes, Colour.

Directed by Terence Davies)

Liverpool was one of Europe's 2008 capital cities of culture. One time resident of Liverpool, director Terence Davies, agreed to make a film for the celebrations, a blend of documentary, cinema poem and symphony and personal memoir. The film, hailed at the Cannes film festival, had its world premiere in October at the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall and was released throughout the United Kingdom on October 31st. Clearly, it played an important role in the consciousness of Liverpool as a capital of culture.

Davies was born in 1945 and his film generally focuses on the years of his life, especially of his childhood. His film is something of a meditation on time and on change.

The 72 minute film begins with a red curtain rising on a screen but then moves to black and white archival footage of early 20th century Liverpool. Davies' use of of archive material enables him to remind his audience of the growth of the port city during its heyday in the 19th century. As his camera slowly sweeps over the many grand architectural sites, we are impressed by how the city saw itself and its importance. However, Davies does not shirk from the grimier aspects of Liverpool and its industrial age heritage. And, as regards architecture, Davies has no qualms in displaying the high rise ugliness of 'developments' from the 1960s.

But, as with Davies' own feature films, it is the people, the poorer people, the workers who merit his attention and time. A great deal of the running time of the film is devoted to detailed footage of ordinary people, especially from the 1940s to the 1960s, the humdrum lives in dingy neighbourhoods, the ugly rows of buildings, the small enjoyments despite the deprivations. By way of relief we see pictures of colourful Sunday excursions to New Brighton, sun-bathing, deck chairs and the fun of the fair.

While Davies makes reference to the war years and the rationing afterwards, it is the effect of the Korean war that gets his attention. Davies uses a great range of music as background to his images but one Liverpool phenomenon that does not meet his approval is the Beatles and the pop music from the 1960s on.

Another aspect of British life that does not meet with his approval is the royal family. He shows some scenes of Princess Elizabeth's wedding and of the coronation of the queen, but he peppers his commentary with unflattering remarks about extravagance at a time of post-war rationing.

However, what receives his greatest disapproval is the Catholic Church of his childhood. Having become a 'born-again atheist' in his teens, he does now know the church of the post Vatican II years. Many Catholics who go to see his film may be quite surprised at his frequent lambasting of the Church.

But, a critic of the Church needs to be listened to. Often the criticism is a cry of anguish concerning perceived treatment by the church or by its officials. This is certainly the case with Terence Davies. His cries are sometimes howls of rage, at other times bitter reminiscences of a time when he believed and prayed. For audiences who have seen his films since the 1970s, especially his trilogy of his childhood, his memories of his abusive father and long-suffering mother in Distant Voices, Still Lives and his own prayer and devotion in The Long Day Closes, this will be a familiar theme. This time it pervades his memoir of Liverpool. Criticism can be offensive but, for people of faith and commitment, it can also be a challenge to how they understand their faith and how they can respond to a person whose cry comes, as the psalm says, out of the depths.

The sticking point for Davies and the church is his sexual orientation. He is more explicit in speaking about it in this film than in his feature films. Coming to adolescence in the late 1950s, at a time when these issues were not spoken about, he tells us that he prayed fervently but received no help. This led to his disillusionment with faith and the church. This pervades his commentary in the film.

Davies seems to be one of those people who, despite his hostility and bitterness, can't seem to let go of the Church. His film has many images, refers to prayers, keeps dwelling on his childhood faith. When he comes to Christ the King cathedral, he shows the building as well as the consecration by Cardinal Heenan. This gives him the chance to make jibes at liturgical dress and the Popes. While they are smart and cleveristic, they remain at the level of cheap shots and offer no depth of comment or criticism. They lead to the thought that Davies has been regurgitating this bile for decades which can only leave a sickeningly bitter taste in his mouth. But, his criticisms should be a challenge, even an examination of the Catholic conscience on how it has treated people, especially the young and the inexperienced, in the past.

Finally, it should be said that Davies has created a film that captures so much of a city, its various times and memories. He has chosen images. He has chosen music. He has chosen beautiful prose and poetry, finally quoting T.S.Eliot at length, especially his Four Quartets – and a prayerful wish for Davies and his obsessive returning to his past would be that like the traveller who goes back to his beginning and discovers it for the first time, Davies could see his past in a new and different light.