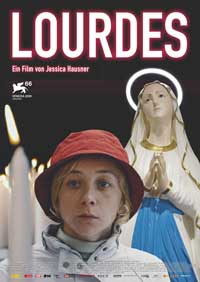

LOURDES

14th September 2009

For almost 150 years, Lourdes has been an important centre for pilgrimage and prayer. The story of Bernadette Soubirous, the apparitions of Mary, the digging of the spring, the abundance of water as well as the many cures and healings are well-known because of the experiences of the faithful, the questions of sceptics like Emile Zola as well as Franz Werfel's book, The Song of Bernadette, and the 1943 film version with Jennifer Jones. Bernadette also featured in two French films, Bernadette (1988) and The Passion of Bernadette (1989), directed by Jean Delannoy, with Sydney Penny in the title role.

The new film, Lourdes, is a project written and directed by Austrian Jessica Hausner who has a Catholic background. However, she does not approach the subject from an explicit Catholic point of view. Rather, she wanted to put on the screen the Lourdes pilgrimage experience and to raise the issues of the nature of God, the possibility of miracles and the 'fairness' of God in granting healing to some and not to others.

The film-makers discussed the project with the bishop of Tarbes, where Lourdes is situated, and received collaboration during the making from the shrine authorities. It is certainly a film Catholics can be comfortable with, the presentation of devotion and faith, the range of perspectives of the pilgrims themselves, the experience of healings. The questions the film asks are those that believers and non-believers must ask.

The film shows a group of French pilgrims, with their chaplain and assistants from the Order of Malta, following the rituals of the visit to Lourdes: the grotto, the Eucharistic blessing, confession, processions, bathing in the water... The central character, Christine, has severe MS and is paralysed. She has come with some devotion but, principally, for a trip. The elderly lady she shares a room with is prayerful and solicitous for her. During the pilgrimage, Christine feels a growing strength and seems to be healed. There are various responses from the group, joy and suspicion, and the film is open-ended concerning Christine's future.

CRITICAL RESPONSE AND AWARDS

Lourdes screened in competition at the Venice Film Festival, September 2009. Critical response, even from reviewers avowedly hostile or wary of Catholicism, tended to be very positive, a surprise in itself. Lourdes won awards from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication (the jury making the point that the award was not simply because of the Catholic topic but also because of the quality of the film and its probing of faith and miracles). The Catholic Ente dello Spettacolo also gave the film its Navicella award.

However, Lourdes also won the award of the Federation of International Film Critics, FIPRESCI, an indication of the merits of the film since this award is made for excellence in film-making as well as for exploration of themes. Yet, the film won no award from the main jury at the Festival. Writer Stephanie Bunbury, The Age, Melbourne, 14th September, suggests that the French were wary of the possibility of miracles and to make an award to Lourdes would be 'unethical'. (She refers to this type of reasoning as 'bone-headed'!)

More puzzling is the fact that Lourdes was given the Brian award. This is an annual collateral Festival prize named after the character, Brian, from Monty Python's Life of Brian. It is made by the association of rationalists and atheists. Did they interpret the film as, minimally, a sceptical look at the phenomenon of Lourdes or, more strongly, as an attack on the 'irrationality' of faith and miracles?

WHAT THE AUDIENCE SEES

For Catholics, Jessica Hausner has presented the Lourdes experience in generally accurate and extensive detail. Cast and crew sometimes mingled with actual pilgrims. (The prelate for the Eucharistic blessing is Cardinal Roger Mahoney of Los Angeles.) Those who have visited Lourdes will have memories stirred. The sequence where Christine speaks of her angers and frustrations to the priest in confession rings true as does the scene in the smaller room where pilgrims ask for personal blessings.

Non- Catholics have been puzzled by as well as in some admiration for what they see. The gathering of the sick seems to some just like one of those revivalist tent gatherings, full of enthusiasm, which have sometimes been exposed as frauds. Confession is often problematic for those who have never participated in it. The touching of the grotto wall, the statues and candles may seem quaintly devout. Outside the precincts of the shrine is the kitsch-commercial paraphernalia of images, candles and souvenirs.

The film's attention to detail will be appreciated by Catholics. It may not lead anyone in the audience, except the devout, to think that Lourdes is a place that they should visit. The sceptics in the audience will generally remain sceptical though they may appreciate better that authorities in Lourdes have procedures and doctors to examine those who think that they have been cured. The psychological benefit of religiously going to such a shrine will be appreciated – believers realising that this can be a personal healing experience in itself.

The screenplay shows a range of characters in the pilgrim group who illustrate these different perspectives: a mother who brings her disabled daughter every year to Lourdes and experiences a momentary improvement only, an old man who is lonely, several severely disabled patients, two gossiping and critical ladies... It is the same with the men and women volunteers with the Order of Malta: the men who are happy-go-lucky and glad to date the women assistants, the severely religious woman in charge who likes discipline and offers her own sufferings for others, the young volunteer who has not developed much compassion and eventually wishes she had gone on her skiing holiday as usual. Christine befriends the officer in charge who is attentive to her but fails her when he thinks she may not be cured.

A great strength of the film is the performance of Sylvie Testud as Christine. As an ill woman, confined to a wheelchair and completely dependent on others, she is both sweet and kind, extraordinarily patient despite her confessing to being angry. She is a woman of faith, joining in the hymns, prayers, visits to the grotto. However, she also wants to socialise, experience the pilgrimage as an outing. Her experience of healing is at first tentative, not immediately very spiritual, an entering into the ordinary, even banal, world of day-by-day. Is this a miracle? Not? Does she deserve this experience? Will it last - and does this matter? Does her experience challenge her deeply? Spiritually?

The priest with the group is down-to-earth (playing cards in the evenings and showing a sense of rhythm in dancing at the social at the end of the stay) but the lines he is given, inside and outside the confessional, tend to be the abstract sayings about God and freedom along with rather facilely quoting texts from the scriptures about completing the sufferings of Christ in our own bodies.

This may be the director's experience of priests but it seems quite a limited experience – a lot more, deeper sayings, could be put into the mouth of the priest or other characters which could offer more intellectually and spiritually satisfying leads and stimulations to understanding what faith, miracles and divine intervention are about. (The Canadian film, La Neuvaine (2005) by Bernard Ermond, set in the pilgrimage shrine of St Anne of Beaupre and raising questions about faith, simple and simplistic faith, rationalism and agnosticism, is a fine example of deeper reflection and how it can be incorporated into the screenplay of a film.)

ISSUES RAISED: GOD, FAITH, MIRACLES.

God

Almost all of the characters believe in God. The characters do not question God's existence. That questioning may be for many in the audience. What the characters do is express different aspects of belief.

One of the difficulties in discussions about God is God's seeming arbitrariness in dealing with suffering people. If God is God, why does God not intervene directly in the world and in people's lives (while we fail to remember how much most of us resent parents and authorities when they do intervene and take away our freedom and freedoms)? The other question is that of suffering – and one needs to reflect on Elie Wiesel's response when asked where was God in the holocaust. His answer suggests that God was in the ovens and with the suffering concentration camp victims.

Jessica Hausner has remarked that one effect of making Lourdes was to make her question more strongly the 'fairness' of God in dealing with different people, favouring some and not others.

Faith

There is an unfortunate presupposition amongst believers and non-believers alike that discussion of faith limits itself to the intellectual aspect of faith: believing what God says, intellectual assent to the truth. This keeps the discussion in the realm of the mind and focuses on ideas, reason and logic.

However, faith is something lived, lived in ordinary day-to-day life as well as in crises. It is what St Paul calls 'faith from the heart'. Faith is a spirituality in action, sometimes heroic, sometimes faint. This is dramatised in the characters in the film but, in the context of the Lourdes experience and people being prone to focus on faith and 'truth' in discussion, drawing attention to this more explicitly without being didactic would have enhanced the film and given more nuanced attention to the characters. The traces can be seen in Cecile, the Order of Malta leader, and her rather ascetical lived faith, and the old lady, pious and kind, who looks after Christine.

Miracles

In the early centuries of the church, miracles were claimed at the drop of a crutch, many of the reported miracles being enhanced storytelling. In the century of 'Enlightenment', the 18th century, Benedict XIV tightened criteria for the acceptance of a miracle. The language was used of an occurrence (generally a cure) being outside the laws of nature. More recent theological reflection highlights another criterion: that the cure take place as a response to and in the context of prayer. Maybe an occurrence is a psychosomatic experience but, in the context of faith and prayer, it can be described as 'miraculous', even though the 'big' miracles are those which seem to transcend the laws of nature.

Bringing this line of thought to what happens in the film, Lourdes, raises interesting issues of whose prayers are answered, whether Christine has experienced something miraculous ('big' or 'psychosomatic') and what is the nature of her spiritual experience – of the healing and its consequences for her life, of the challenge to her intellectual faith and to her faith from the heart, of her witnessing God's healing love and power?

There are some suggestions in the film – and Jessica Hausner does not want to make a propaganda film – but visitors to Lourdes have testified that they have experienced so much more of this faith from the heart which transcends previous experience.

Clearly, there can be a religious interpretation of the film as well as a secular interpretation (from SIGNIS award criteria to those for the Rationalist and Atheist Brian award). Believers will appreciate that this film is 'out there' in the world marketplace, a stimulus to discussion – and, maybe, an invitation to something more.

SIGNIS STATEMENT (Abbreviated)

14th September 2009

LOURDES

The new film, Lourdes, is a project written and directed by Austrian Jessica Hausner who has a Catholic background. However, she does not approach the subject from an explicit Catholic point of view. Rather, she wanted to put on the screen the Lourdes pilgrimage experience and to raise the issues of the nature of God, the possibility of miracles and the 'fairness' of God in granting healing to some and not to others.

The film-makers discussed the project with the bishop of Tarbes, where Lourdes is situated, and received collaboration during the making from the shrine authorities. It is certainly a film Catholics can be comfortable with, the presentation of devotion and faith, the range of perspectives of the pilgrims themselves, the experience of healings. The questions the film asks are those that believers and non-believers must ask.

The film shows a group of French pilgrims, with their chaplain and assistants from the Order of Malta, following the rituals of the visit to Lourdes: the grotto, the Eucharistic blessing, confession, processions, bathing in the water... The central character, Christine, has severe MS and is paralysed. She has come with some devotion but, principally, for a trip. The elderly lady she shares a room with is prayerful and solicitous for her. During the pilgrimage, Christine feels a growing strength and seems to be healed. There are various responses from the group, joy and suspicion, and the film is open-ended concerning Christine's future.

WHAT THE AUDIENCE SEES

Non- Catholics have been puzzled and some admiration for what they see. The gathering of the sick seems to some just like one of those revivalist tent gatherings, full of enthusiasm, which have sometimes been exposed as frauds. Confession is often problematic for those who have never participated in it. The touching of the grotto wall, the statues and candles may seem quaintly devout. Outside the precincts of the shrine is the kitsch-commercial paraphernalia of images, candles and souvenirs.

The film's attention to detail will be appreciated by Catholics. It may not lead anyone in the audience, except the devout, to think that Lourdes is a place that they should visit. The sceptics in the audience will generally remain sceptical though they may appreciate better that authorities in Lourdes have procedures and doctors to examine those who think that they have been cured. The psychological benefit of religiously going to such a shrine will be appreciated – believers realising that this can be a personal healing experience in itself.

The priest with the group is down-to-earth (playing cards in the evenings and showing a sense of rhythm in dancing at the social at the end of the stay) but the lines he is given, inside and outside the confessional, tend to be the abstract sayings about God and freedom along with rather facilely quoting texts from the scriptures about completing the sufferings of Christ in our own bodies.

A great strength of the film is the performance of Sylvie Testud as Christine. As an ill woman, confined to a wheelchair and completely dependent on others, she is both sweet and kind, extraordinarily patient despite her confessing to being angry. She is a woman of faith, joining in the hymns, prayers, visits to the grotto. However, she also wants to socialise, experience the pilgrimage as an outing. Her experience of healing is at first tentative, not immediately very spiritual, an entering into the ordinary, even banal, world of day-by-day. Is this a miracle? Not? Does she deserve this experience? Will it last - and does this matter? Does her experience challenge her deeply? Spiritually?

APPENDIX:

ISSUES RAISED: GOD, FAITH, MIRACLES.

God

Almost all of the characters believe in God. The characters do not question God's existence. That questioning may be for many in the audience. What the characters do is express different aspects of belief.

One of the difficulties in discussions about God is God's seeming arbitrariness in dealing with suffering people. If God is God, why does God not intervene directly in the world and in people's lives (while we fail to remember how much most of us resent parents and authorities when they do intervene and take away our freedom and freedoms)? The other question is that of suffering – and one needs to reflect on Elie Wiesel's response when asked where was God in the holocaust. His answer suggests that God was in the ovens and with the suffering concentration camp victims.

Jessica Hausner has remarked that one effect of making Lourdes was to make her question more strongly the 'fairness' of God in dealing with different people, favouring some and not others.

Faith

There is an unfortunate presupposition amongst believers and non-believers alike that discussion of faith limits itself to the intellectual aspect of faith: believing what God says, intellectual assent to the truth. This keeps the discussion in the realm of the mind and focuses on ideas, reason and logic.

However, faith is something lived, lived in ordinary day-to-day life as well as in crises. It is what St Paul calls 'faith from the heart'. Faith is a spirituality in action, sometimes heroic, sometimes faint. This is dramatised in the characters in the film but, in the context of the Lourdes experience and people being prone to focus on faith and 'truth' in discussion, drawing attention to this more explicitly without being didactic would have enhanced the film and given more nuanced attention to the characters. The traces can be seen in Cecile, the Order of Malta leader, and her rather ascetical lived faith, and the old lady, pious and kind, who looks after Christine.

Miracles

In the early centuries of the church, miracles were claimed at the drop of a crutch, many of the reported miracles being enhanced storytelling. In the century of 'Enlightenment', the 18th century, Benedict XIV tightened criteria for the acceptance of a miracle. The language was used of an occurrence (generally a cure) being outside the laws of nature. More recent theological reflection highlights another criterion: that the cure take place as a response to and in the context of prayer. Maybe an occurrence is a psychosomatic experience but, in the context of faith and prayer, it can be described as 'miraculous', even though the 'big' miracles are those which seem to transcend the laws of nature.

Bringing this line of thought to what happens in the film, Lourdes, raises interesting issues of whose prayers are answered, whether Christine has experienced something miraculous ('big' or 'psychosomatic') and what is the nature of her spiritual experience – of the healing and its consequences for her life, of the challenge to her intellectual faith and to her faith from the heart, of her witnessing God's healing love and power?

There are some suggestions in the film – and Jessica Hausner does not want to make a propaganda film – but visitors to Lourdes have testified that they have experienced so much more of this faith from the heart which transcends previous experience.